Pardon that terrible title, but I do promise to explain what it means.

I chose to reflect on Funes & Mackness’s aritcle “When inclusion excludes: a counter narrative of open online education”, as the narrative presented in the article pointed to a problem with inclusive education which has been frustrating me as of late. In summary, Funes & Mackness argue that the trope of total inclusion is not feasible (2017), and the aspiration of finding the model of total inclusion is developed from a particular sense of social justice (2017). They focus this theory around online education, pointing to the many exclusionary qualities of the online environment, such as silencing those with a minority opinion (the democratizing effect), requiring capital and infrastructure to access the online environment, and having to know (and follow) the unsaid etiquette rules present in online communication (2017). All the while, of course, online education is touted as the most distributed, transparent, and open delivery platform.

I take their point, especially when considering my own educational program. I have already seen members of my cohort engaged in twitter feuds with other educators, where the notion of privileges and bias have been used as ad-hominem attacks on their arguments. Frankly, such an occurrence was saddening, yet unsurprising; previous course material in our program was to read In Public: The Shifting Consequences of Twitter Scholarship by Bonnie Stewart, who experienced (watched) a similar situation during her PhD research.

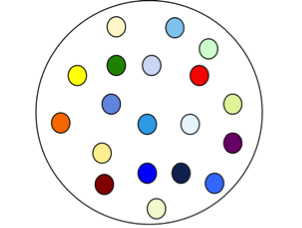

There is a relationship between Funes & Mackness and my thoughts on the British Columbian narrative around inclusive education, specifically total inclusion (2017), as mentioned earlier. I currently work in Greater Victoria School District as a grade eight teacher. I have found my district to offer quite a vast amount of professional development opportunities and it continues to remain heavily committed to inclusive learning, living up to its catch-phrase “One Learning Community” (Greater Victoria, 2016). The district has been heavily focused on the work of Shelley Moore, an inclusive learning specialist who has developed resources and presentations in order to train teachers how to best include all students (UBC Graduate Studies, n.d.). In my district, it is now normal to see a photo of the inclusion dots (Figure 1) on a weekly basis. The dots represent students, while the circles represent classroom spaces.

The latest rendition of the diagram includes the 5th circle (Figure 2) depicting every student in a class as diverse, not necessarily conforming to a certain way of being or learning:

I have various concerns about this model I believe it embodies the “total inclusion” problem Funes & Mackness were referring to. The latest professional development seminar I attended featured Moore describing how the fifth circle (Figure 2) had been sparked by one of her students arguing that the inclusion circle (Figure 1) was in fact not inclusion, but assimilation (trying to make all of our students green). I took issue with that epiphany; what exactly are we trying to do as educators? We can teach all the curriculum, but are we not also responsible for preparing our students for real-world realities? As students move through our education system, the complexity of what they must learn increases, and the skills and competencies they must have become specific to workplace/institutional expectations. Bluntly, our educational system should make green dots, because our socio-economic system wants the green dots.

I want to be very careful in my framing my opinion on this, as it is specific to educational skills. I’m not arguing against a diverse community in or out of a classroom or in society in general, nor would I celebrate any system promoting assimilation. The total destruction of an identity/society to conform to a perceived superior one is assimilation. Attempting to guide our students to embody consistent, conventional academic skills and competencies is not.

This begs the question; if i concede that Moore is correct in that we are engaging in assimilation by trying to shape them into a particular mold, perhaps she should drop the British Columbian government (ministry of education) as a partner? From the ministry’s Vision for Student Success: “Our education system will enhance our efforts to prepare all students for lifelong learning, encourage the use of technology, and be prepared for graduation with practical expectations informed by employers and post-secondary institutions [emphasis added]” (n.d.).

In summary, wile Funes & Mackness’s work was focused on the online branch of education, I find their ideas to be applicable to the whole inclusive theory. Perhaps there is a need to have hard discussions over what we are really trying to accomplish in inclusive education. Is inclusion really meant to be total from beginning to end and beyond, ignoring the likelihood of inconsistent acquisition of conventional abilities? Or can it be shifted to promoting an importance of universal accessibility at the beginning of content acquisition, terminating with a consistent set of standards our students aim to achieve?

Ironically, I cower at having the hard discussions. I wonder if the majority of #bcedchat participants would think that my point of view should be excluded from what is understood as the correct discussion topics regarding inclusive learning.

References

Funes, M., & Mackness, J. (2018). When inclusion excludes: A counter narrative of open online education. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(2), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1444638

Greater Victoria School District Strategic Plan—The Greater Victoria School District No. 61. (n.d.). Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.sd61.bc.ca/our-district/about-us/greater-victoria-school-district-strategic-plan/

Moore, S. (n.d.). Blogsomemoore. Blogsomemoore. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://blogsomemoore.com/

Shelley Moore: Transforming Inclusive Education for Students with Significant Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in Secondary Schools. (n.d.). UBC Graduate Studies. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.grad.ubc.ca/campus-community/meet-our-students/moore-shelley

Stewart, B. (2015, April 14). In Public: The Shifting Consequences of Twitter Scholarship. Hybrid Pedagogy. https://hybridpedagogy.org/in-public-the-shifting-consequences-of-twitter-scholarship/

Vision for Student Success—Province of British Columbia. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/administration/program-management/vision-for-student-success

Leave a Reply